|

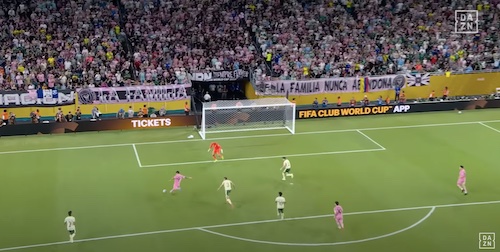

By Paul Oberjuerge Global soccer has rediscovered the United States national soccer team, in large part because the U.S. team rediscovered itself. Returning to a formation — and to tactics — that fit America’s soccer spirit and talent, the U.S. shocked Spain, 2-0, in a Confederations Cup semifinal on Wednesday, a result that halted Spain’s world record 15-match winning streak and its world-record-tying 35-match unbeaten streak. Rest assured, the entire soccer world knows about this. From Bloemfontein, South Africa, site of the match, to Blackpool and the Black Sea. Europe’s club teams are on hiatus. The Confederations Cup has the world stage almost to itself, and the U.S.-Spain game had to be must-viewing for out-of-season fans starved for some footy. A perfect time to come up with a great result against the world’s No. 1-ranked team. The Americans now get a rematch with Brazil in the championship match on Sunday. Brazil thrashed the U.S., 3-0, in group play of what organizers and FIFA like to call a Tournament of Champions, but that was before American coach Bob Bradley got his players back to what they do best: Playing a cautious, defense-first, 4-4-2 alignment and relying on the counterattack to produce goals. It seems odd, in retrospect, that Bradley didn’t think of this sooner, given that the slow U.S. climb to international respectability, going back at least to the early 1990s, was founded on absorbing pressure in the defensive end and then springing to the attack when space and numbers allowed. Luckily, he came back to it against Spain, a supremely confident, attacking squad that had not tasted defeat since losing a friendly to Romania in November of 2006. The American-style 4-4-2 works best against opponents that want to come forward but are not particularly big or physical. Like, say, Spain. The U.S. perfected its style against Mexico and continues to use it against El Tri to this day. Mexico still hasn’t figured out that dashing itself upon a defense with eight men in or near the box doesn’t lead to many goals but does, in fact, yield counterattack possibilities to the hated Yanqis. (Remember the 2-0 U.S. victory over Mexico in the 2002 World Cup? Mexico apparently doesn’t.) The counterattacking 4-4-2 fits American spirit because it demands 90 minutes of gritty defense, and American teams never have shied away from hard labor on a soccer pitch. It fits American talent because it requires height and strength in the box, and the U.S. always has that, this time in the figures of Oguchi Onyewu, Jay DeMerit and Carlos Bocanegra. It also calls for midfielders, especially on the wings, who can switch over to the attack but also will sprint back on defense so the back eight can regain its shape. Such as Landon Donovan and Clint Dempsey, who along with central defender Michael Bradley were the top three players in the tournament in miles run during group play. Some key points in the match, and how they pertain to Bob Bradley’s tactics: –Spain came out attacking, and the U.S. seemed a bit disconcerted by the speed and ingenuity of the assaults. But the Americans did not give up the (almost inevitably fatal) early goal because they never lost their shape in the back. –The U.S. took advantage of Spain’s almost arrogant preference for throwing forward players from the back. Specifically, right back Sergio Ramos, who was overly keen to get into the attack — leaving gaps behind him. The U.S. exploited one of those gaps for its first goal, from Jozy Altidore in the 27th minute. With Ramos caught upfield, U.S. forward Charlie Davies controlled a ball near the touch line about 35 yards out, and passed it ahead to Dempsey. Dempsey spotted Altidore single-marked near the top of the box, and threaded the ball up to him. Altidore is a big and strong target-forward sort of player, and with Ramos out of the play and Spain’s center backs out of position, Altidore was defended by Spain’s smallish left back, Joan Capdevila, who made an awful decision to try to lever his body around the well-muscled Altidore. Altidore held off Capdevila, controlled the ball, turned for the goal — and had no one between him and the net aside from keeper Iker Casillas. Altidore took a stride or two and unleashed a hard, low shot toward the left post, before Carles Puyol could come over to stop him. The ball deflected off Casillas’ hand as he went to ground about 6 yards off his line, and the ball settled into the side netting. Bang. U.S. 1, Spain 0. –After an hour of defending, with Tim Howard in the back to parry any chances his defenders and midfielders couldn’t block/deflect/deter, the U.S. got the clincher on another counter. With Spain’s defenders retreating into position, substitute midfielder Benny Feilhaber won a ball in the attacking half, moved forward and spotted Landon Donovan surging forward on his right. Feilhaber rolled the ball to him, wisely ignoring Altidore in the box, who was in an offside position. Donovan carried the ball into the right side of the box and could have taken a shot, probably should have, but Casillas had a clear view of him and is no slouch, so Donovan decided to cross the ball toward Dempsey, on the left. But there was too much traffic for it to work cleanly, as it had in the 3-0 victory over Egypt. The ball was deflected by Bernard Pique and settled at the feet of Ramos, near the far post. Ramos apparently was unaware that Dempsey was standing just behind him, and as Ramos turned and gave the ball only the slightest touch, Dempsey pounced, lunging into a hard shot that went into the back of the net in the 74th minute. From there, it was back to choking off the Spanish attack. There were nervous moments. More than a few. Spain amassed 29 shots, to nine by the U.S., and had 17 corner kicks to three by the Americans. But Howard was called on to make only a few acrobatic saves. Most of the rest of the shots were half-chances in traffic, often deflected or rushed by all those Yanks in white jerseys around the ball. Just as Bradley had planned. Just as the Americans have done before against Latin teams committed to the attack. When full time was whistled, the U.S. bench sprinted out to the pitch and the Americans celebrated in a way no one could have anticipated a few days before, when the U.S. had lost 3-1 to Italy and 3-0 to Brazil. Bocanegra, the Rennes defender and U.S. captain, spoke to FIFA.com about the U.S. defense. "It’s a big day for us and one of the biggest moments in our history," Bocanegra said. "It’s hard to believe right now; it hasn’t really sunk in. "There were a lot of acrobatic, sliding blocks," he said. "One guy would be sliding in to clear the shot away, and another guy would come in behind to clean it up. The defense was amazing, but it wasn’t just the defenders. The whole team worked to slam the door shut." Some called it the greatest victory in U.S. history. In terms of the whole-world-watching, it would be. But the 1-0 victory over England in the 1950 World cup was a more shocking result, and the 1-0 victory at Port of Spain, Trinidad, in 1989 — that put the U.S. in the World Cup for the first time in 40 years — was more significant. Next, a rematch with Brazil, which needed a Daniel Alves goal in the 87th minute to beat back host South Africa in the other semifinal. Donovan said the U.S. will be prepared. "We just beat the best team in the world, so we’re going to be very fired up no matter who we meet in the final," Donovan told FIFA.com. "It’s great to reach a FIFA final for the first time, but we’ve played a lot of finals in our region. We won’t feel any new pressure in this final here. We’ll be ready to go." Will the rediscovered U.S. Way to Win work against Brazil? Keep eight back, defend, defend, defend, move forward selectively and track back immediately? Perhaps not. Brazil is more inventive than is Spain, a bit bigger and technically a near-equal. The U.S. strategy comes unhinged if the opposition scores an early goal, and Brazil certainly is capable of that, with Kaka and Robinho in the attack. However it turns out, the tournament has been as useful as any U.S. fan could hope for. Matches against the world’s top-ranked team (Spain), the No. 5 team (Italy) and two against the No. 4 team (Brazil). What better way for Bradley to see what his players can do in a pinch against elite competition? What better proving ground for rediscovering lost tactics and getting a team into its best possible position to succeed? Paul Oberjuerge writes about soccer for the NY Times soccer blog Goal. He can be reached at: paul.oberjuerge@gmail.com |

US National Team Rediscovered Itself